Bucharest’s Road to Beijing Goes through Washington

As with many other Eastern and Central European nations, Romania has consistently considered its relationship with the United States to be a privileged one: a strategic partnership meant to mitigate the risks of a neighboring assertive Russia. Nonetheless, while some countries from this region have also hedged their bets by taking a welcoming position towards China (Eurasia Daily Monitor, April 30; Eurasia Daily Monitor, June 10), Romania has maintained a very cautious—and reluctant—position in dealing with Beijing, even before China’s recent heightened tensions with the United States rose to prominence on the global scene.

Of course, Romania has cultivated polite and formally cordial relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC)—both at a bilateral level, and within multilateral formats such as the “16+1” framework (China Brief, February 15; China Brief, May 29). However, trade and investment links have been maintained at only a limited level, compounded by a reticence to develop a politically relevant partnership. In this sense, Romania did not really align itself with a broader Central European trend of warming up towards Beijing. Bucharest has not witnessed a significant increase in Chinese economic activity (either in terms of investment or corporate takeover), as has been seen in Hungary, the Czech Republic, or Slovakia (CHOICE, August 22). Chinese investors have generally kept a low profile in Romania, and even the few joint projects that have been the subject of discussions have failed to materialize.

In addition, since the advent of the trade conflict between China and the United States, Romania has taken an even more cautious stance towards Beijing—prioritizing instead its relationship with Washington, and showing little desire to cause any frictions with its North American ally. This has especially been the case since Vice President Pompeo’s quite explicit hints in his February 2019 Central European tour—during which Pompeo spoke to the need to choose one’s political (and economic) friends very carefully (Radio Free Europe, February 11; U.S. Department of State, February 10).

The latest meeting between the Romanian and American presidents at the White House in August bears witness to these policy orientations (Radio Free Europe, August 21). Although the encounter largely went unnoticed in the circles of China observers, it is nonetheless very relevant for predicting a pattern that is gradually emerging in this region: bringing forth the necessity for Central and Eastern European countries to take an open stand by those that they consider allies.

The Writing is on the Wall: The Perils of (Chinese) 5G

While the timing of the August meeting might have touched upon pre-election domestic campaigning—Mr. Iohannis is facing new presidential elections this year in Romania—it also dealt with fundamental issues in Romania’s security architecture and the consolidation of its strategic partnership with the United States. As always, there were many points on the agenda: NATO, the implicit Russian threat, energy, anti-corruption efforts, and economic relations. Without spending too much time on the bilateral trade balance—negative and on the rise, but still negligible in overall value (Business Review, November 21, 2018)—the two presidents managed to discuss a range of important security issues.

Unsurprisingly, the most salient topic was NATO’s Eastern Flank and its consolidation in the context of the Black Sea’s intensive remilitarization (implicitly connected to concerns over Crimean annexation and its transformation into a full-fledged Russian base of operations). However, after this expected main point, the joint statement emerging from the meeting particularly mentioned that the two countries “seek to avoid the security risks that accompany Chinese investment in 5G telecommunications networks” (Joint Statement, August 20) (hereafter “Joint Statement”). This statement offered no mere hints or euphemistic reading-between-the-lines; it was instead a direct reference to Chinese companies that operate in the international telecommunications market. Furthermore, the point was listed as a security challenge at the top of the list concerning key bilateral issues.

It was later reported by the Romanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs that an additional memorandum concerning 5G technology was also signed, intended to allow “a rigorous evaluation of suppliers for fully ensuring the security in the implementation of 5G technology” (Calea Europeana, August 22). While no particular company was mentioned, concerns were mentioned regarding transparency, security, and the rule of law, referencing the so-called Prague Proposals (Prague Proposals, May 3). Interpreting the content of this memorandum, the head of the national telecom authority in Romania (ANCOM) argued that review of 5G issues would clearly involve a more proactive role for the Supreme Council of National Defense, a body chaired by the President (RFI Romania, August 21). Reading between the lines, as Huawei was supposed to be an important equipment supplier for many telecom operators, its case would need careful consideration—and the Chinese telecom giant’s prospects in Romania look rather bleak in the near future.

Energy as National Security: It’s Not Only About Russia

The Joint Statement also made the clear assertion that “[t]he United States and Romania recognize that energy security is national security.” This led to an explicit criticism of the Nord Stream 2 project for increasing the dependency of regional allies upon Russia’s supply of gas (Joint Statement, August 20; Eurasia Daily Monitor, November 14, 2018). In the case of Romania, such assertions must be analyzed in a larger context—one in which China features as a minor but relevant actor.

In the last decade, Beijing has made some incremental steps in becoming a more active player in the Romanian energy market—be it in the form of traditional exploitation and power generation, or in the alternative (“green”) sector. Beyond photovoltaic parks and plans to refurbish existing power-plants (or even develop new ones), the main discussion has been centered around one very important event: the 2015 decision by state-owned CEFC China Energy (中国华信能源, Zhongguo Huaxin Nengyuan) to acquire a majority shareholding in KazMunayGas International from its Kazakh owners (Rompetrol, April 29, 2016). This acquisition would have allowed CEFC to gain control over Rompetrol (owned by KazMunayGas International), a major oil company in Romania and the owner of the country’s largest refinery (Petromidia).

However, when the entire CEFC story unraveled—and company chairman Ye Jianming (叶简明) virtually disappeared, under investigation in China (China Brief, May 9)—the deal for Rompetrol also failed to materialize (RISAP, August 30, 2018). There was no longer any delicate decision for the Romanian authorities to make. Nonetheless, the PRC interest in taking on a greater role in the region’s energy architecture cannot be presumed to have waned, and that is why the Joint Statement is very relevant in this context. Identifying energy issues as national security challenges presents a much greater role for Romania’s Supreme Council of National Defense in reviewing transactions that involve natural resources. Prospective Chinese investments will likely be placed into an unpredictable limbo in regards to their potential access to one of the most promising energy markets at the edge of the European Union.

The Nuclear Option: On (Responsibly) Choosing One’s Friends

A third issue that has a bearing upon Romania’s economic relations with the PRC pertains to the dilemma of developing new generation capacities in Romania’s aging nuclear plant at Cernavodă, located near the southeast Black Sea coast. While the U.S.-Romanian Joint Statement merely asserted that “[w]e further urge our industries to work closely together to support Romania’s civil nuclear energy goals” (Joint Statement, August 20), this text appeared in the context of a larger discussion within Romania. Romania’s sole nuclear plant in Cernavodă is a project dating back to the final decade of Communist rule; it has two operational units and is reliant upon Canadian technology. In the late 2000s, a quest for building two additional units began, with multiple offers that came to no fruition.

In 2015, a memorandum of understanding was signed for a joint venture (a public-private partnership) with the PRC state-owned enterprise China General Nuclear Power (CGN); the value of said deal was estimated by some to be almost $8 billion (Economica, June 6; World Nuclear News, May 8). In 2019, a preliminary investment agreement was signed in the presence of officials from both countries, prompting the Chinese ambassador to state that “[t]he Chinese government will work together with the Romanian government for the nuclear power project to start as soon as possible, setting a good example for pragmatic cooperation between the two countries” (Xinhua, May 8).

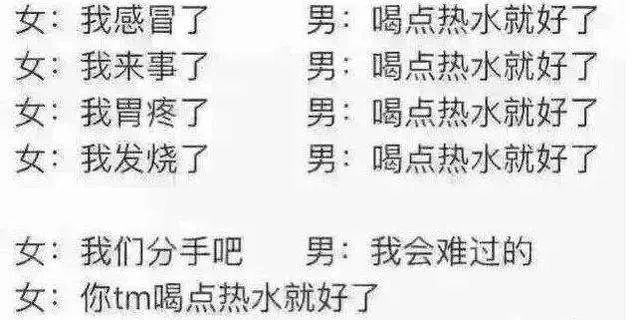

Image: The Cernavodă Nuclear Plant in southeastern Romania, which dates back to a joint Romanian-Canadian project commenced in the 1980s. A memorandum of understanding was signed in 2015 for the PRC state-owned China General Nuclear Power Corporation (CGN) to enter into a joint venture to continue construction on the facility—with a subsequent preliminary agreement signed in May 2019—but work at Cernavodă under these agreements has yet to begin. (Source: CGN)

This deal seemed like a classic Belt and Road offering, but with a strategic twist. Influential voices in Romania—such as former President Traian Băsescu—promptly manifested their dissent against allowing a state-owned Chinese company to gain control over a part of Romania’s energy production capacities, and “becoming dependent on China’s nuclear technology” (Mediafax, May 16). The situation appears to be even more complicated, as CGN has been recently placed on the “entity list” by the U.S. Department of Commerce, effectively barring the company from acquiring products and technologies from American firms on grounds that it had “engaged in or enabled efforts to acquire advanced U.S. nuclear technology and material for diversion to military uses in China” (Department of Commerce, August 14).

Therefore, based upon the contexts of Romania’s continuous emphasis on its strategic partnership with its North American ally and its renewed pledge to closely align on global challenges (including energy matters), it is a safe bet to say that cooperation with Chinese entities that have been ‘blacklisted’ in the United States—such as CGN—shall also be reviewed by Romania in terms of national security, possibly leading to a discontinuation of the Chinese investment project.

Conclusion: Sending a Regional Message to Central and Eastern European States

The August meeting between the U.S. and Romanian presidents needs to be understood in an extended strategic environment, not merely in bilateral terms. Its implications pertain to the larger regional—and global arena, in which Russia and China have been designated as challengers to the established system of international order. Thus, it must be taken into consideration that the Joint Statement reflects much more than a lofty communique uttered in diplomatic parlance, especially in the context of an increasing trade conflict with China.

This document was the first official Romanian declaration that directly referenced and singled out “Chinese investment in 5G” as a potential problem. Furthermore, it was meant to show Romania’s resolution in attaining joint strategic objectives together with the United States. At the same time, given the ambiguous relations that some other American allies in the Central and East European region maintain with China, it sent a clear signal in a diplomatic realm that is sometimes immersed in duplicity. Thus, it was not really a message for Beijing, and not merely another episode in an ever-escalating trade conflict—rather, it was a blueprint for America’s regional allies, and a statement on the necessity to take an unequivocal stance regarding relations with China.

Horia Ciurtin is an Associate Expert at the New Strategy Center (Bucharest, Romania), a Research Fellow for the European Federation for Investment Law and Arbitration (Brussels, Belgium), and ad External PhD Researcher at the Amsterdam Center for International Law (Amsterdam, Netherlands). He also serves as a legal consultant in the field of international investment law throughout the Balkans and CEE. He recently published the study entitled “A New Era in Cross-Strait Relations? A Post-Sovereign Enquiry in Taiwan’s Investment Treaty System”, in Julien Chaisse (ed.), China’s Investment Three-Prong Strategy: The Bilateral, Regional, and Global Tracks, Oxford University Press, 2019. Contact him at h.a.ciurtin@uva.nl.